| Regions | New Netherland • East Indies |

| Patronage | Merchant-class |

| Contrast with | Western realism |

| Key movements | Batik Opulent • Javanese Baroque • Hudson Valley Mannerism |

| Key characteristics | Abstract • Symbolic • Decorative • Globally interconnected • Diverse cultural influences |

The art produced in the colonies of the New Netherland, East Indies, and other European overseas territories during the 17th-19th centuries was remarkably distinct from the colonial art of the British Empire or French Colonial Empire in our own timeline. Rather than simply reflecting European artistic traditions transplanted to foreign lands, colonial art in this alternate history represented a vibrant synthesis of indigenous, Asian, and European influences that gave rise to highly original and influential aesthetic movements.

The Dutch colonies, particularly the wealthy trading hubs of New Rotterdam (New York) in New Netherland and the Dutch East Indies, were the centers of gravity for colonial art in this era. Here, wealthy merchant-class patrons, rather than aristocratic or religious institutions, provided the primary funding and patronage for the arts.

One of the most significant artistic traditions that emerged was Batik Opulent, a style of textile design and decoration that combined Dutch Golden Age painting techniques with the intricate wax-resist patterning of Javanese and Malay batik. Batik Opulent fabrics became prized luxury goods traded globally and inspired imitation across Europe.

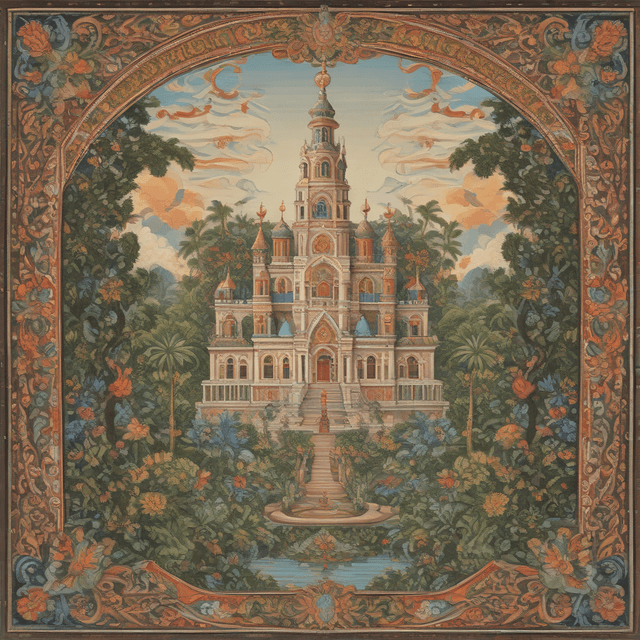

The Dutch colonies also saw the rise of a unique architectural style known as Javanese Baroque, which married ornate Dutch façades with the curving rooflines, intricate woodcarvings, and symbolic motifs of traditional Javanese temple architecture. Major examples can be found in cities like Batavia (Jakarta) and Semarang.

Unlike the more insular colonial art worlds of the British or French, the Dutch colonial sphere was highly interconnected, with artistic influences flowing freely between Asia, the Americas, Africa, and Europe. This produced a remarkable cross-pollination of styles.

For instance, the Hudson Valley Mannerist painters of New Netherland, while rooted in Dutch Baroque traditions, incorporated motifs and techniques from the Iroquois, Lenape, and other Native American societies they encountered. The resulting paintings featured stylized, almost abstract depictions of the natural world and Native life.

Similarly, the ornate lacquerware and porcelain produced in the Dutch East Indies drew on Chinese, Japanese, and indigenous Indonesian ceramic traditions, but were designed to appeal to European tastes and traded globally. These luxury goods in turn influenced the development of Delftware and other European ceramic styles.

While often overlooked in mainstream art history, the vibrant and innovative colonial art worlds nurtured within the Dutch overseas empire left an indelible mark on global visual culture. Batik Opulent textiles, Javanese Baroque architecture, Hudson Valley Mannerism, and other distinctive modes of artistic expression demonstrated the creative potential that emerged from the cross-pollination of European, Asian, and indigenous traditions.

These colonial artistic legacies can still be felt today, from the patterns and designs of high fashion to the eclectic mix of architectural styles found in modern cities. The fluidity and interconnectedness that characterized Dutch colonial art anticipated the globalized world of the present day, making it a prescient forerunner to our contemporary visual landscape.